Hi, and welcome back to China Report!

If you are on Twitter and follow news about China, you likely have heard a pretty wild rumor recently: that President Xi Jinping was under house arrest and that there was about to be a major power grab in the country.

First of all, let me be very clear: this report is false and should not be taken seriously. No credible sources on China have bought it. It’s wishful thinking at best, and intentional disinformation at worst.

But it’s interesting to dissect how a ridiculous rumor could be elevated and spread so widely that it made it to Twitter’s deeply flawed trending list over the weekend. So today I’ll trace it back to its roots and unpack how it gained traction.

The story basically went through three stages, brewing in Chinese circles before being translated into English by influencers opposed to the Chinese government and finally being amplified by Indian Twitter accounts.

Stage 1: It’s not rare to see such salacious political rumors if you follow a lot of Chinese-language Twitter accounts. There’s a whole world of commentators and anonymous accounts openly speculating about every faint signal coming out of China’s state media, magnifying every word and gesture, and interpreting it as something groundbreaking.

The rumor that’s going around this time had the benefit of coinciding with a few real news events that were combined into a narrative that may look plausible to people unfamiliar with China. Here are the things that actually happened: (1) a Chinese general, Li Qiaoming, left his commander post after five years, and it hasn’t been reported where he’s heading; (2) a 105-year-old retired high-ranking politician made a rare media appearance to talk about respecting the elders; (3) domestic flights in China were experiencing high cancellation rates—as high as 60% last week; (4) Xi hadn’t appeared in public since he returned from Uzbekistan on September 16.

These were all the materials that conspiracy theorists needed to somehow conclude that Xi must have been under house arrest initiated by the general and the party elder. That story first started circulating among Chinese-language accounts on September 22.

(All these real goings-on likely have much more boring explanations. For example, spiking flight cancellations have actually been common this year, as many Chinese cities have experienced unpredictable covid-related lockdowns. In the three weeks before the rumor started, the weekly flight cancellation rates were 60.1%, 69.0%, and 64.1%, according to a Chinese flight tracker app. But for people who aren’t familiar with how badly daily life has been disrupted in China, the rates seemed like an abnormality right before the 20th National Congress, an event organized every five years to elect the top officials of the Chinese Community Party.)

Stage 2: On September 23, the story broke out of Chinese-language Twitter when it was translated into English by Jennifer Zeng, an activist and self-proclaimed journalist, who has a track record of spreading rumors and misattributed videos.

As a TV host for New Tang Dynasty Television and a contributor to the Epoch Times, both of which are backed by the anti-China religious group Falun Gong, Zeng is a key player in a media network that plays an increasingly important role in conspiracies about China and also about elections in the US. She’s been careful to consistently present the coup story as a “rumor,” but she has since put out over a dozen tweets about it, continuing to drum up speculation.

Stage 3: This is perhaps the most interesting development. Several separate analyses of Twitter activities on the #ChinaCoup hashtag found that starting September 24, a large number of Indian Twitter accounts picked up the report and spread it far and wide.

For example, one analysis of over 32,000 Twitter interactions by Marc Owen Jones, an assistant professor at Hamad bin Khalifa University in Qatar, who researches disinformation and digital media, shows that @Indiatvnews, the account of the Indian nationalist TV channel, is the largest disseminator of the coup rumor. Subramanian Swamy, a prominent Indian politician followed by 10 million people, also talked about the story in several tweets on September 24, describing it as “new rumor to be checked out.”

India has the third-largest number of Twitter users in the world. Considering the long-standing geopolitical tensions between India and China, plus the relative lack of knowledge that average Indians likely have about Chinese politics and how to discern Falun Gong–backed media accounts, it’s not necessarily surprising that they fell for and spread the rumor.

Despite several recent reports on the rise of bot activity originating in India, there’s not yet enough evidence to determine whether this was a coordinated effort to push the coup rumor. There are suspicious signs, like “a lot of new accounts as well as the fact some of the key influencers now [are] suspended,” Jones told me. “This does not necessarily point to it being state-backed—just a lot of inauthentic activities.”

Of course, since this is Twitter, many other accounts are capitalizing on the popularity of this discourse and in turn further amplifying the story. This includes people intentionally trolling unsuspecting users by pairing old videos with the new rumor, and some users in Africa are hijacking the hashtag to gain visibility for their own content—apparently a long-practiced trick among users in Nigeria and Kenya.

By Monday, the rumor had mostly died down. While Xi still hadn’t shown up, recent documents reaffirmed his participation and influence in the coming party congress, demonstrating that he’s very much still in power.

The fact that a completely unsubstantiated rumor, one that basically happens every other month in Chinese Twitter circles, could grow so big and have tricked so many people is both funny and depressing. The bottom line: Social media is still a mess full of misinformation—but you may not notice that mess if you are not familiar with the issue being discussed.

What’s your thought on the development of this rumor? Write to me at zeyi@technologyreview.com

Catch up with China

More than 1,400 US-trained Chinese scientists left their US institutions for Chinese ones in 2021—a 22% jump from the year before. (Wall Street Journal $)

- A major reason they’ve left has been the “China Initiative,” a discontinued effort by the US Department of Justice to go after academics for suspected espionage risks. (MIT Technology Review)

One of the first businesses to feel the weight of Queen Elizabeth II’s passing? China-based flag producers. (Associated Press)

Hong Kong officially ended its mandatory hotel quarantine policy, hoping to regain its status as Asia’s financial center. (BBC)

A bipartisan group of US lawmakers is working to ban YMTC, a Chinese company that makes chips for flash drives and hard drives. (Financial Times $)

- This could complicate things for Apple, which has confirmed it is considering sourcing flash memory chips from YMTC. (Financial Times $)

China’s top livestream e-commerce influencer has quietly resumed streaming to his 60 million followers after a political controversy. (What’s on Weibo)

- I wrote about his mishap in June; it was the latest development in a year-long power reshuffle that saw three of the top Chinese influencers disappear for regulatory reasons. (MIT Technology Review)

The US and Russia are neck-and-neck in a battle over whose candidate will lead the obscure but incredibly important International Telecommunication Union for the next four years. Unsurprisingly, China is throwing its support behind Russia’s pick. (The Interpreter)

Lost in Translation

The death of a unicorn

As a deep dive in the Chinese business publication LatePost documented this summer, it only took 10 years for the Chinese flexible-screen startup Royole to rise to an $8 billion valuation and then fall to the brink of bankruptcy. Founded by Liu Zihong, Royole was once a star to investors and the technological leader in flexible and foldable screens, which you’ve probably seen recently in fancy smartphones from Samsung or Motorola. But the company could never quite crack the demand issue. It also made the mistake of trying to become a smartphone brand itself; its smartphone model—technically “the first foldable-screen phone in the world”—was a big failure and made the company a weak competitor rather than a key supplier to other phone makers. Instead of a startup fairytale, Royole became a cautionary tale for other wannabe tech unicorns that could be dreaming too big.

One More Thing

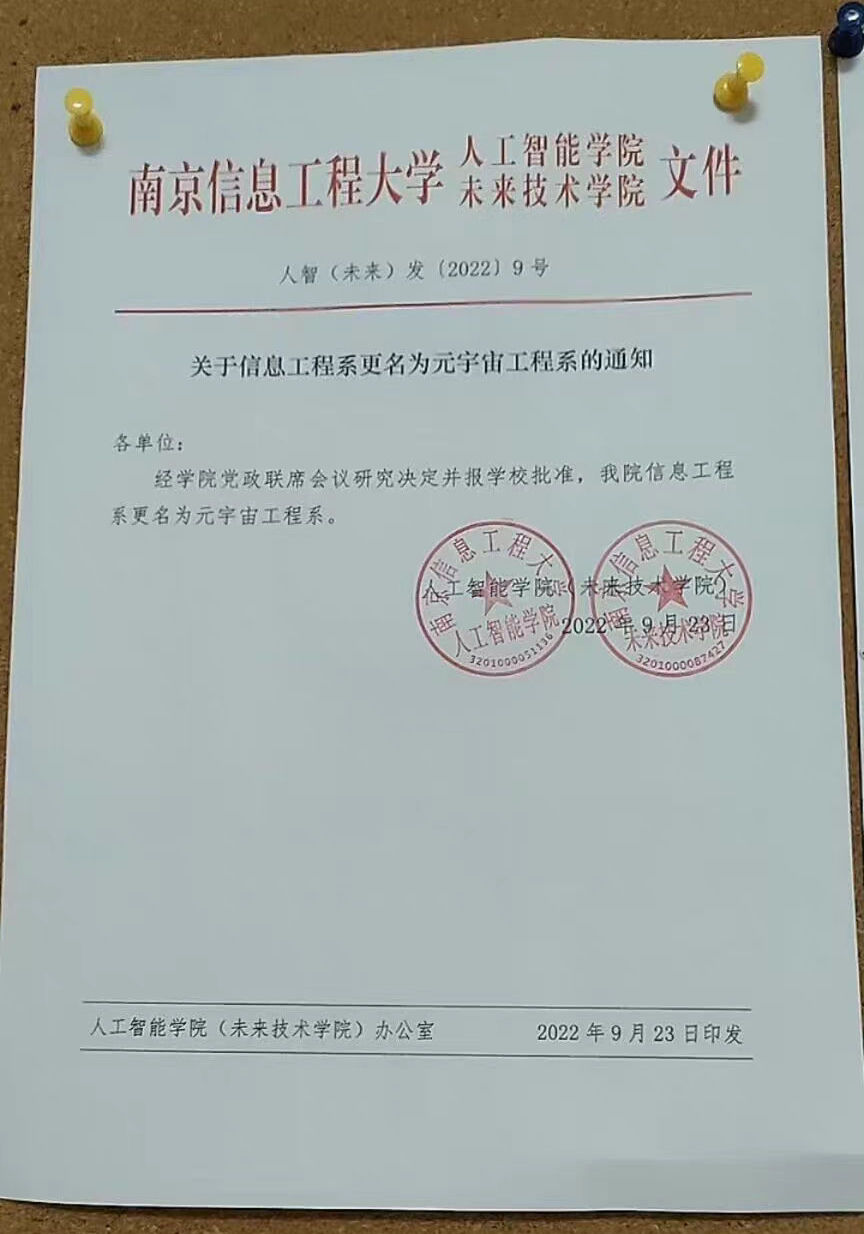

You can now get a degree in metaverse studies in China. On September 23, the Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology officially renamed its Information Engineering Department the Metaverse Engineering Department. This is the first university in China to do so, and the school says it’s planning to offer master’s and doctoral degrees in metaverse studies too. Maybe by the time the first wave of PhDs graduate, we will finally have legs in the metaverse.

from MIT Technology Review https://ift.tt/kKvmgSx

via IFTTT

Comments

Post a Comment